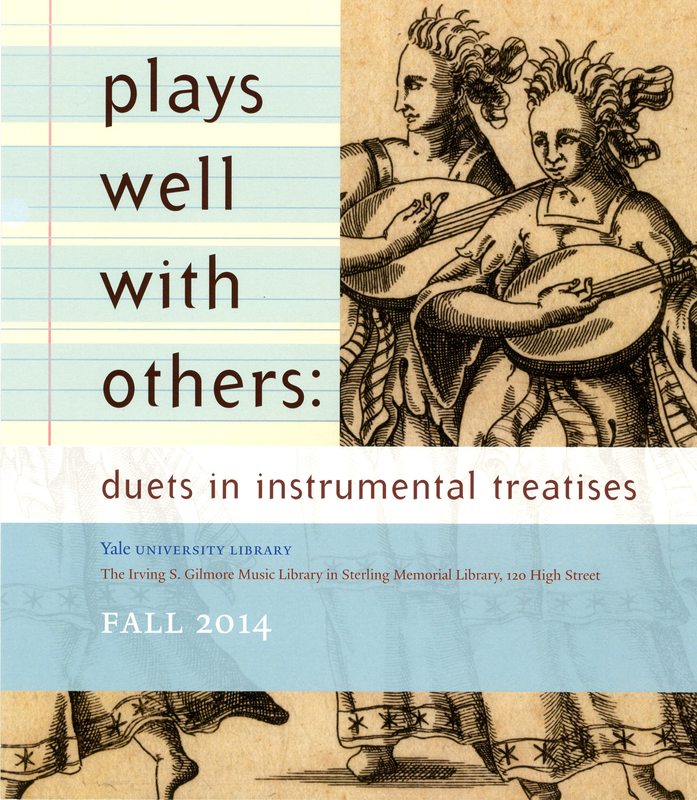

Plays Well with Others: Duets in Instrumental Treatises

Introduction

Since at least the invention of bicinium, two-part vocal or instrumental compositions of the Renaissance and early Baroque, duets have been an integral part of learning to play an instrument or sing, and have been included in most etude, method, and music theory books for at least six centuries. Who better than flutist and composer Johann Joachim Quantz to explain why:

...whoever wished to be, or to become, a musician cannot accustom himself to harmony too soon. If concertos and solos are undertaken prematurely, the risk is run of becoming unsure in time, and uneven and ragged in execution. One can easily get into the habit of either rushing or dragging; one does not learn the correct execution of suspensions as quickly: and the reason is that no counter-motion is heard in another part; or, even if the master plays another part with you, because in a concerto the full harmony is not heard, and in a solo often not enough motion is heard to keep yourself in time. And when, with much anguish and difficulty, a concerto has finally been learned by heart, as soon as one wishes to play it with the full accompaniment, one seems to be transported in a different realm. All of these inconveniences fall way, however, if duets have been practiced for a while. Then, on the foundation of the good and correct execution laid through them, whatever else is required in the way of speed, extempore variations, and such matters, can be cultivated with much less effort in the practice of concertos and solos. [Emphasis mine]

As a teacher of the horn, I couldn’t have put it better myself. This exhibit is a small sampling of duets in instrumental method books.